Lust is often reduced to sexual temptation or physical desire, but the Christian tradition presents a deeper and more profound understanding. Lust is not only a misuse of sexuality—it is a distortion of human relationships because it denies the full personhood of another. Rather than seeing another as a subject with dignity, autonomy, and a soul created in the image of God, lust reduces the person to an object for personal pleasure. This paper will explore this understanding through Scripture, the story of David and Bathsheba, and the writings of Augustine, Aquinas, and Pope John Paul II.

Jesus first reveals the interior dimension of lust in Matthew 5:28: “Anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart” (New International Version). Here, lust is presented as more than outward behavior; it is an inward posture that treats another person as an object. Lust damages not only purity but also love—because it turns a person into something to be taken, rather than someone to be loved.

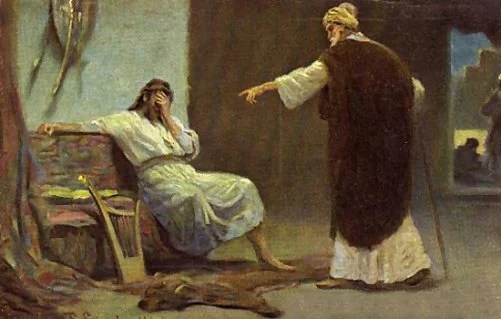

The story of David and Bathsheba (2 Samuel 11) shows lust as more than uncontrolled desire. In that moment, David did not consider Bathsheba’s dignity, her marriage, or her autonomy. He also ignored his responsibilities as king and his covenant with God. His sin was not simply sexual; it was relational and moral blindness. Bathsheba became a means to satisfy his desire rather than a person made in God’s image. This narrative supports the idea that lust is not only about the body but is fundamentally about a failure to love.

Saint Augustine describes this failure through the concept of uti (use) and frui (love). In The City of God, Augustine explains that sin occurs when we love ourselves in a disordered way (amor sui) and use others rather than love them properly (Augustine, 1998). Lust, then, is not only physical appetite; it is self-centeredness that consumes others for emotional or physical gratification. It is love turned inward, refusing to see others as God sees them.

Saint Thomas Aquinas further develops this idea by defining lust as a disordered passion that clouds reason. In the Summa Theologica, he writes that lust treats the other’s body as a tool for pleasure, rather than honoring the unity of body and soul that makes each human being a person (Aquinas, 1920). When reason is overshadowed by passion, the will no longer seeks the good of the other but only personal satisfaction. Thus, lust becomes not only a sin against chastity but also a sin against justice and charity.

Pope John Paul II, in his Theology of the Body, emphasizes that lust “abolishes the dignity of the gift.” Human beings are meant to be gifts to one another, capable of self-giving love. Lust, however, breaks this dynamic by turning the other into a possession or an instrument (John Paul II, 2006). Instead of mutual love, lust creates domination, consumption, and emotional detachment. For John Paul II, the opposite of lust is not the absence of desire but the presence of love that sees the whole person—body and soul.

Therefore, in Christian thought, the true problem with lust is not desire itself—desire is part of human nature. The problem is when desire becomes detached from love and responsibility. When it blinds a person to the humanity, relationships, story, and soul of another, it ceases to be love and becomes sin. Lust is a failure to see others as God sees them—beloved, sacred, and free. It is the rejection of another’s autonomy for the sake of self-centered pleasure.

In conclusion, lust is far more than sexual temptation. It is the distortion of love into use. Scripture, the story of David, and Christian theological tradition all point to this truth: lust is not only bodily sin but relational injustice. It is a choice to ignore another person’s dignity and to reduce them to an object. The Christian answer is not repression but conversion—learning to see others not as objects of desire, but as persons worthy of love.

References (APA 7th Edition)

Aquinas, T. (1920). Summa Theologica (Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Trans.). Benziger Brothers.

Augustine. (1998). The City of God (H. Bettenson, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Holy Bible, New International Version. (2011). Zondervan.

John Paul II. (2006). Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body (M. Waldstein, Trans.). Pauline Books & Media.

New International Version Bible. (2011). Zondervan.

(2 Samuel 11). The Holy Bible.

Leave a comment